In my publications I have explored issues of style, emotion, poetics, time and space, rhythm, subjectivity, and creative ethnographic writing. Below are conceptual overviews of my work with links to articles, chapters, and books.

Style

My early writings on this topic drew from about two-and-a-half years of fieldwork on Karnatak music in Madurai and Chennai (1982-1988). The notion of bāṇi in South India connotes both a musical style and a socio-musical entity. Using the Karaikkudi bāṇi of vīṇā playing as a case study, I explored the varied ways in which such performers as Karaikkudi Lakshmi Ammal, Rajeswari Padmanabhan, Ranganayaki Rajagopalan and K. S. Subramanian had articulated their membership in the bāṇi. Style/school in South India cannot be reduced to a set of common technical or musical features but rather grows from the diversity of ways in which disciples understand their relationship to their masters. These relationships include familial bonds as well as commonly held aspects of behavior and specific playing techniques. This view of “style” is meant to counter those that pertain exclusively to art objects, clothing, and so forth, and which tend to focus on static elements held in common rather than on social processes.

1991

“Style and tradition in Karaikkudi vina playing.” Asian Theatre Journal 8(2): 118–41.

Emotions

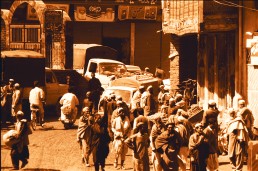

My theoretical contribution to the study of music and emotion lies in the idea of musical “emotive” and its role in what I call emotional contour and texture. The theory is grounded in my fieldwork on ceremonies of the Kota tribe in South India and public Islamic observances in South Asia (mainly Shī‘ī and Sufi). In my 2001 article, “Emotional dimensions. . .,” I draw upon William Reddy’s concept of the emotive as a distinctive type of verbal utterance, whereby the utterer undergoes emotional transformation as result of making a self-referential emotional statement. For example, saying “I am sad,” does not just describe one’s emotional state, it also contributes to one’s experience of sadness. Certain kinds of pieces or gestures function musically as emotives when members of a society have assigned highly conventionalized emotional meanings to them, either through naming or associating them with moments in a ritual process. In ceremonial contexts such as those of the Kotas, performances of particular musical pieces and other rituals serve as emotional guideposts, framing or suggesting changing emotional associations in time. Because the actual experiences of individuals may differ from the idealized representations of emotional meaning, I identify a dynamic in which Kotas perform music pieces and individuals react idiosyncratically, knowing but perhaps not feeling the conventional associations of the pieces, and experiencing each emotional nuance to a different degree. Each ceremony can be viewed as a timeline articulated by musical and other emotives. I term the sequences of responses of any one experiencing subject over time as the “emotional contour” of a ceremony. Envisioning the emotional contour as a strand, the multiple strands that make up the complex responses to conventionalized musical gestures over time weave together what I call the “emotional texture” of a ceremony.For the Kotas, I focus on the major ceremonies of god and death, the “god ceremony” (devr) and the secondary mortuary ceremony or “dry funeral” (varldāv), each of which exhibits a variety of emotional nuances that are guided, in part, by music. Interest in the emotional complexity of funerals cross-culturally (where deaths are, to various degrees, both mourned and celebrated) led me to focus on the affectively multivalent ceremony of Muharram in North India and Pakistan. Muharram commemorates the battle in 680 C.E. between Husain (son of the Prophet, Muhammad) and his party, and the henchmen of the Ummayad Caliphate. Contemporary observances of Muharram in South Asia may include special drumming patterns, songs, tuneful poetic recitations that are not considered songs, and instrumental music.

My 2003 article “Return to tears” draws from the two case studies cited above and considers the broad socio-political forces and historical trends affecting the ways both Kotas and observers of Muharram display their mourning in public contexts in South Asia. I show that in both cases, there has been a broad move from affective complexity and diversity in the performance of nominally sad events to a more narrow set of activities that are more clearly and unambiguously “sad.”

My 2005/6 and 2014 monographs and 2000/2001 article on mourning songs further explore affective themes.

The Voice in the Drum: Music, Language and Emotion in Islamicate South Asia. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014)

The Black Cow’s Footprint: Time, Space and Music in the Lives of the Kotas of South India (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2005; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.)

2003

“Wolf Return to Tears” In, The Living and the Dead: Social dimensions of death in South Asian religions, 95–112, ed. Elizabeth Wilson. Albany: State University of New York Press.

2001

“Emotional dimensions of ritual music among the Kotas, a south Indian tribe.” Ethnomusicology 45(3): 379–422.

2000/01

“Mourning songs and human pasts among the Kotas of south India.”Asian M. 32(1): 141–183.

2000

“Embodiment and ambivalence: Emotion in south Asian Muharram drumming.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 32: 81–116.

Poetics

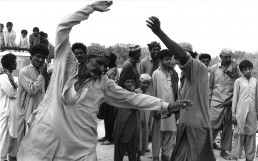

Scholars have used the term poetics variously to describe techniques for constructing a literary work, allude to an artistic twist in social action (giving rise to the popular pair of terms “politics and poetics of. . .”), and draw attention to the manipulation of form (as in Jakobson’s “focus on the message for its own sake”). Aristotle, Roman Jakobson, Michael Herzfeld and many others have drawn attention to parallelism and its social analog, mimesis. Significant are the differences between the object of parallelism and the new utterance or action, which is seen as a meaningful deformation of it. I have expanded the discussion from language and social action to embrace aspects of music and dance. In my 2006 article, I show how musicians and dancers relate with one another, worship God, identify with interconnected Sufi saints, and activate local codes with respect to gender, language, and classical music in contemporary Pakistan.

The voice in the drum dilates on this theme with respect to Muharram observances and practices of Sufism elsewhere in South Asia.

2006

“The Poetics of ‘Sufi’ Practice: Drumming, Dancing, and Complex Agency at Madho Lāl Husain (And Beyond).” American Ethnologist 33(2): 246-268. (Reprinted 2010 in Islam and Society in Pakistan: Anthropological Perspectives, ed. Magnus Marsden. Karachi: OUP)

The Voice in the Drum: Music, Language and Emotion in Islamicate South Asia. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014)

Space and Time

The Black Cow’s Footprint: Time, Space and Music in the Lives of the Kotas of South India (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2005; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.)

2010

“Music and translocation in south Asia: Two case studies.” In Relationship between Eurasia and Japan: Mutual Interaction and Representation. Proceedings of the international symposium, Performance and Culture: Exchange and Symbols in Eurasia and Japan (held on March 28-29, 2009), 116-121, ed. by Koike, Jun’ichi, Shoji Ueno, Yoshitaka Terada and Ryoji Sasahara. Tokyo: National Institutes for the Humanities.

The Black Cow’s Footprint is an ethnography of music, ritual, and everyday life among the Kotas of South India. It explores ways in which Kotas create aspects of themselves and their social relations through activities taking specific spatiotemporal forms: “Anchoring,” latching on to and organizing events around selected moments and places; “centripetence,” moving physically and morally to the center and de-emphasizing differences; “centrifugality,” moving outward from the village and drawing attention to the identity of the individual; and “interlocking,” formally joining complementary social and musical components. “Anchoring” pertains both to moment-to-moment musical decision-making and long term calendrical planning. A spatio-temporal anchor is a reference point with a gravitational field, a field of potential for changing other events. In Kota instrumental music, particular strokes in a drum pattern serve as anchor points for the double-reed players who perform rhythmically elastic melodies. The double-reed player must speed his melody up or pull it back to align melody notes with drum strokes. The potential for other kinds of anchor points to effect surrounding events can be seen, for example, in calendrical planning. The timing of a holiday is likely to affect a family’s travel plans, lead members to take additional days off of school or work, make time sensitive financial decisions and so forth. A broader implication of the book is that scholars may refine notions of “identity” through the analysis of subjective and intersubjective spatiotemporal forms (“spacetime”). Processes such as anchoring are culturally specific in their details but broadly shared across cultures as potential ways in which all humans orient themselves in space and time.

Rhythm

My writings on rhythm concern the relationship among elements of a performance, ways of describing rhythmic elasticity, and the status of “rhythm” vis-à-vis percussion parts. In the Black Cow’s Footprint I developed the notion of “anchor points” to describe the ways in which players of the double-reed koḷ coordinate their flowing melodies with cyclical drum patterns (see “space and time”). In my 2010 article on the rhythms of rāga ālāpana, I point out a lacuna in South Indian theorizations of their classical music, namely the failure to account for the rhythmic organization of ālāpana, which is often described as rhythmically free. I show not only that ālāpana follows a steady pulse, but also that aspects of the rāga itself are understood in temporal and not only tonal terms. Theorizations of rāga in South India focus mainly on tonal content, although every musician is intuitively aware of the subtle aspects of timing that make rāga expositions both musical and technically correct. In my book The voice in the drum, I argue against the tendency to equate “rhythm” with the percussion section in an ensemble. Instead, following a number of scholars, I suggest that drumming and conventional melodies (i.e. those articulated by the voice, piano, violin etc) are both kinds of melodies, the former “stroke melodies” and the latter “tone melodies.” Both kinds of melodies are equally defined by rhythm.

The book then proceeds to analyze the kinds of rhythmic thinking that go into creating and naming drum patterns across South Asia, taking into account musical examples and terminology in Tamil, Telugu, Kota, Hindi, Urdu, Sindhi, Seraiki, Panjabi and Dumaki. Many South Asian performers conceptualize drum patterns in terms of unevenly distributed stressed strokes rather than in terms of the equally spaced pulses typical of beats-in-a-measure thinking in Western music. In some cases sequences of stressed strokes mark out verbal phrases such as slogans and lines of classical poetry.

The Voice in the Drum: Music, Language and Emotion in Islamicate South Asia. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014)

The Black Cow’s Footprint: Time, Space and Music in the Lives of the Kotas of South India (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2005; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.)

2010

The rhythms of rāga ālāpana in south Indian music: A preliminary introduction. 121-141. Perspectives on Korean Music:Sanjo and Issues of Improvisation in Musical Traditions of Asia. vol 1.

Subjectivity and Ethnographic Creative Writing

My writings on emotion, spacetime, and poetics all concern subjectivity in that they concern the manifold ways in which individuals may experience the world. However, The Voice in the Drum approaches issues of subjectivity differently. In this book I chose to frame my ethnographic research on ritual drumming and Islamic ritual in the form of a novel. I created a fictional character, named Ali, and followed the development of his career as a journalist and later as a scholar. In the course of his life, Ali encounters the subjects of my fieldwork, speaking in their own voices and very often identified by their actual names. In conventional ethnographic accounts, it is generally not appropriate to attribute thoughts and feelings to social actors based on their behaviors. We may intuit aspects of our field consultants’ inner worlds, and we can interpret their statements (if any) about their thoughts and feelings, but it would be wrong to think that fieldwork truly allows us to get inside anyone else’s head. One of the reasons I chose to frame the book as an interaction between fictional and real characters was in order to explore a set of ethnographically plausible inner thoughts and feelings, without pretending that I could attribute them to any particular person. Through Ali’s moments of introspection, conversation, and note-taking, the reader has the opportunity to view several possible ways of interpreting drumming and other kinds of musical activities in Sufi and Shī‘ī contexts. The fact that any fictional account must be “true” to particular historical and cultural contexts, and the contingencies of this and all fieldwork, raises questions throughout concerning what it means to be a “real” and “fictional” character in this book.

Contact

richard@richardkwolf.com

Music Building

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

02138